Over the past two years, Stephen Tardif has been arrested nearly 50 times on charges ranging from disorderly conduct to burglary.

Almost as often, he’s back out on the street within days, sometimes hours, after posting bail or being released on his own recognizance. But it’s usually not long until police are dealing with him again.

Tardif’s case is one of several in the Lewiston-Auburn area in recent months that have frustrated police and prosecutors who say repeat offenders are let back onto the streets much too easily, consuming time and resources, and putting the public in danger.

Changes over the years to Maine’s bail system, they say, have led to a revolving door for people who continue to commit crimes and violate conditions of release, leaving law enforcement and residents to deal with the fallout.

“The unintended message from the criminal justice system is that there is no accountability for certain criminal behavior, and dangerously, those who chose to engage in this criminal behavior are picking up on this message,” said Neil McLean, district attorney for Androscoggin, Oxford and Franklin counties.

Others, however, say judges are asked to weigh a variety of complex factors when setting bail — decisions that can be life changing for the defendant — and generally do a good job. They say the public shouldn’t focus on a few outlying cases amid the thousands in which bail conditions are followed.

“A few aberrations create the impression of systemic failure, even if the majority of defendants comply,” said Justice Donald Alexander, a retired longtime jurist in Maine. “Courts, law enforcement and prosecutors must work together to enforce conditions effectively while preserving constitutional rights.”

Most agree, however, that with Maine’s jails overcrowded and criminal caseloads backed up in the courts, the bail system needs significant changes.

THE WAY IT’S SUPPOSED TO WORK

From arrest to release, the justice system ideally works like this: When a crime is committed, the suspect is arrested, charged and either held in jail or released on bail, which is meant to ensure the suspect returns for court appearances.

After an arrest, law enforcement officers request the presence of a bail commissioner, who sets the initial bail based solely on the current charges. The defendant then appears before a judge at the first court appearance, typically within 48 hours, where bail may be confirmed, reduced or increased at a judge’s discretion.

Typically, nonviolent offenders receive low bail, while violent offenders who could pose a threat to safety or are at high risk of flight are given higher bail.

Everyone acknowledges the system isn’t perfect, but local authorities say that in cases of nonviolent crime and violent crime, things have gotten worse.

Case overloads and jail overcrowding have some calling for looser bail rules and releasing more defendants charged with minor crimes, while others say too many offenders are being let out on bail to offend again.

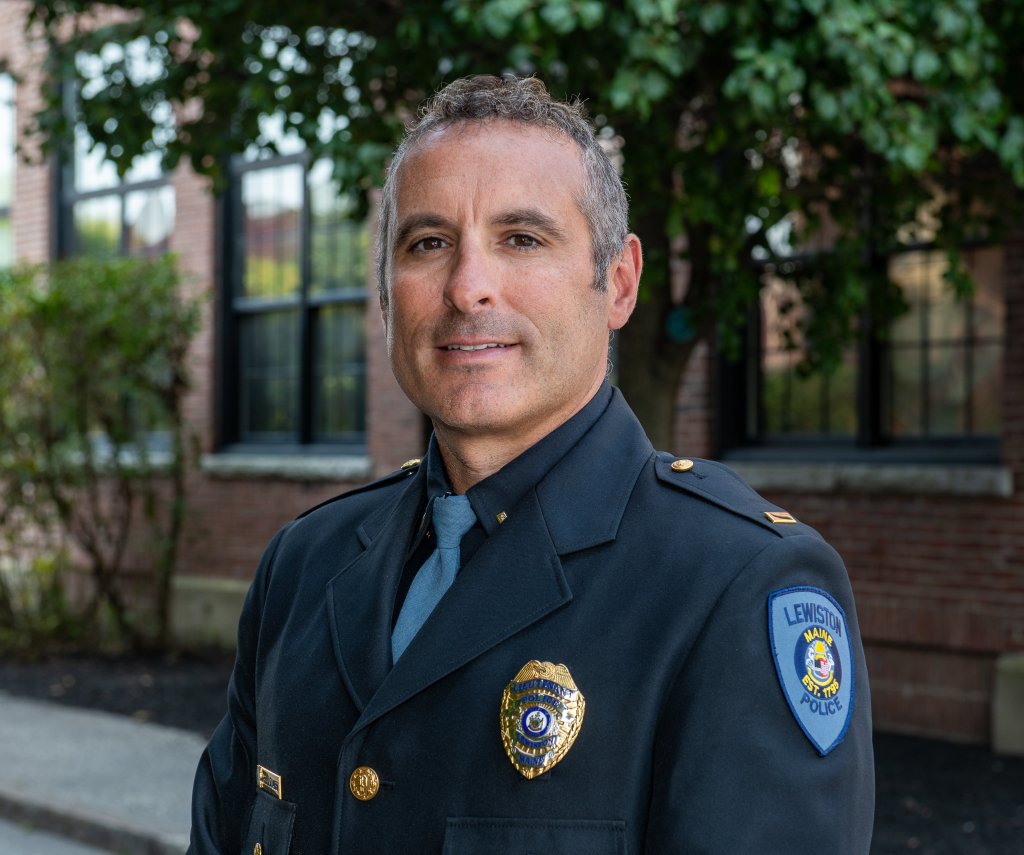

“From our side, we have seen a noticeable uptick in repeat offenders cycling through the system for some time now, often for similar charges,” said Lt. Derrick St. Laurent, Lewiston Police Department’s public information officer. “It’s something officers on the beat are definitely aware of and frustrated by as well.”

Cases like Tardif’s and Devin Skehan’s frustrated others in the community, too.

Skehan was arrested in connection with several dine-and-dash incidents in Lewiston and Auburn this summer, continuing behavior he’d allegedly exhibited in Florida.

But Skehan was released on low bail, as little as $100 in one instance, allowing him to continue his pattern.

Androscoggin County Sheriff Eric Samson, who has been with the office since 1991 and was first elected sheriff in 2014, said that’s common.

“Certain individuals (with a) history of criminal conduct and violations of bail are in and out on a weekly basis for low-level crimes,” Samson said.

“The people that are released from jail aren’t released based on what the sheriff or any law enforcement wants,” Samson said. “In prior years, if we’d make an arrest for violation of bail there would be no (more) bail until the arrestee went before a judge. (Now), with a few exceptions, cash bail can be set on arrest and it’s usually minimal as it’s a low-level offense.”

Bail violation, it’s no surprise then, is the most commonly charged crime in Maine.

WHEN IT GOES WRONG

The Leein Hinkley case shows the stakes at play when a judge sets bail.

In May 2024, Hinkley was in jail facing felony-level domestic violence charges and a probation violation for a previous domestic violence conviction.

After waiting three weeks for a court-appointed lawyer — the result of longtime shortage of attorneys for the indigent in Maine — District Judge Sarah Churchill lowered Hinkley’s bail, saying that his constitutional rights had been violated.

Hinkley was released June 12, 2024. Two days later, against the conditions of release, he returned to his former partner’s residence on Russell Street in Auburn. By the end of the night, two homes burned to the ground, a man was dead and Hinkley was shot and killed by police.

Hinkley’s bail had been reduced despite warnings from McLean’s office and law enforcement.

Critics of the decision included Gov. Janet Mills.

“Based on the facts of the case and my experience as a former defense attorney, district attorney, and attorney general, I strongly disagree with the judge’s decision,” Mills said in a written statement at the time. “In my view, given the severity of the charges, the defendant’s criminal history and the serious danger he posed, these important, competing interests were not properly balanced in this case.”

A joint news release from the Maine Fraternal Order of Police and Maine State Troopers Association blamed Churchill’s decision for Hinkley’s carnage.

“If Leein Hinkley had remained incarcerated as he should have been, the events of June 15 would not have taken place,” the statement said. “(The ruling was) a blatant disregard for the safety of a victim of domestic violence and public safety.”

Maine’s current shortage of public defenders has delayed hearings and affected pretrial decisions. Samson acknowledged delays sometimes contribute to longer jail stays for those waiting for their first appearances or for case resolutions.

McLean, the district attorney, agreed. “A lack of attorneys to represent defendants leads to individuals being released on bail that might not otherwise have happened,” he said. “My office continues to request bail and file MTRB (motions to revoke bail) based on our assessment of public safety needs.”

In March, Superior Court Justice Michaela Murphy ordered the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services to find attorneys for indigent defendants within two weeks, warning she would release those left waiting longer.

Lewiston attorney James Howaniec warned that without the manpower and resources to move through over 30,000 criminal complaints each year, the problem may soon worsen. He noted that Maine’s budget for indigent legal defense is projected to run out by April 2026, leaving potentially hundreds of defense attorneys unpaid for months.

“The court system is in a constitutional crisis and the powers that be have their heads in the sand,” he said.

JUDGES’ DISCRETION

In addition to the constitutional issues of public representation and a speedy trial, judges have to consider numerous other factors when they set bail.

Alexander, a former justice on the Maine Supreme Judicial Court who currently serves on the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services, said judges rely on a statutory checklist that includes the likelihood a defendant will appear in court, their potential danger to the public and community ties.

Judges also consider the facts of the alleged offense, input from attorneys and extenuating circumstances like employment and mental health needs.

Cases like Hinkley’s, prosecutors and law enforcement argue, illustrate why judges must weigh not just past behavior but the potential severity of future crimes.

This is where motions to revoke bail come in, McLean said. A MTRB asks a judge to administer a hold without bail when there is probable cause an offender has committed a new offense while on release. The tool is meant to prevent further criminal conduct.

However, McLean noted that judges sometimes allow defendants to remain free on new bail, a practice he said that often runs contrary to the intent of bail standards, which are to prevent repeat offending and protect “the integrity of the judicial system.”

“Individuals are … (in some cases) ending up free on two, three, four or more bails at the same time,” McLean said. “This discretion seems to be exercised much more frequently than in the past, frustrating law enforcement and the public because repeat offenders can prove they won’t comply with bail conditions, yet continue to be given opportunity after opportunity.”

Alexander said a judge’s quandary is evenly applying a combination of risk assessment, practical experience and professional judgment with a goal of releasing people who can safely return to the community and reliably return to the court.

“We all make evaluation errors,” Alexander said.

“(Poor decisions are) something that comes with the territory if you’re a judge,” he added. “You’re going to make an evaluation each time. But, far more often than not, I think most judges are right most of the time.”

CONSEQUENCES OF BAIL DECISIONS

Samson, McLean and others believe those bail decisions by judges have become more lenient than in the past, frustrating law enforcement and eroding public trust.

There’s a general acknowledgement among law enforcement officials and prosecutors interviewed that many offenders do not pose a serious threat to the public and that the courts cannot detain everyone who violates minor conditions or fails to appear in court.

But they feel that repeated violations or concerning patterns should trigger stricter measures.

“Individuals become emboldened, they lose basic respect for law enforcement and the rule of law generally, and over time, they often graduate to more dangerous crime,” McLean said.

Samson said this approach often frustrates law enforcement and the public because “repeat offenders can just keep bailing out, which complicates our efforts to maintain public safety.”

Skehan, for example, had prior minor offenses, but continued to be released on bail.

There’s another factor to consider as well, St. Laurent said. “There is also a growing concern among many officers that if the judicial system fails to address repeat offenders appropriately, members of the community may feel compelled to take matters into their own hands,” he said.

“This is a dangerous path and one we all want to avoid,” he continued. “Our goal is always to uphold the law professionally and fairly, and we rely on the broader justice system to support that mission.”

Barbara Cardone, director of legal affairs and public relations for the Maine Judicial Branch Administrative Office of the Courts, said the judicial branch rarely comments on the system.

But she noted, “We’re all working to make (bail) better under the current system,” adding that it would be difficult to point a finger in any one direction to identify the source for recidivism problems.

RISK ASSESSMENT

Two factors some judges unofficially consider in setting bail are caseload and jail overcrowding, which are straining Maine’s criminal justice system. Justice Alexander acknowledged that Maine judges are aware of those factors and he couldn’t rule out that some judges don’t consider those factors in some bail decision.

“We simply don’t have the room in the jail or the room to process cases, and it’s inconsistent with our constitutional laws regarding bail to just say, ‘Well, this person did a bad thing, so don’t let them out,’” Alexander said. “That would be a violation of our ethics as judges. You have to make an evaluation every time.”

Overall, judges are always balancing legal criteria with reality, he said. They rely heavily on risk assessment; while most cases are not violent, courts must anticipate worst-case scenarios.

He said those accused of domestic violence and assault and those who are repeat offenders require more careful examination. The challenge with property crimes, on the other hand, is balancing fairness with jail limitations, he said.

Most minor violations are handled informally, he said, but judges also monitor a defendant’s patterns. While judges can increase the consequences for repeated violations, they still have to weigh other factors.

Consequences for violating bail conditions depend on the type of offense. Felony and domestic violence violations usually lead to immediate detention and a hearing, Alexander said. Nonviolent offenses usually lead to new bail rather than automatic detention.

“Most minor violations are handled without a formal hearing,” Alexander said. “But judges track patterns. Repeated offenses may trigger escalated consequences.”

The system aims to be fair and predictable, Alexander said.

But cases like Skehan, Tardif and Hinkley demonstrate how a few offenders can dominate public conversations about bail and pretrial release even though most follow their release conditions, he said.

ANOTHER PERSPECTIVE

While police and prosecutors say Maine’s bail code too often lets repeat offenders walk free, defense attorney Howaniec has a different perspective: Bail isn’t just outdated, it’s discriminatory, leaning heavily against the poorest of citizens, he said.

“I have seen people sit in jail for months because they couldn’t post $500 bail,” Howaniec said, adding that many defendants enter guilty pleas knowing their cases may not otherwise be resolved for months or, in some cases, years.

The bail code, he said, needs fundamental reforms focusing on rehabilitative services rather than incarceration for nonviolent offenders. “Inmates sit around doing nothing all day long besides playing cards and watching TV in claustrophobic, overcrowded jail pods,” he said.

A state commission on bail reform once proposed several progressive changes, Howaniec said, but they were ignored by elected officials who continue to fail to address what he sees as the underlying issue: poverty.

In his four decades of practicing law, including representing indigent clients, Howaniec said he has seen how minor crimes can escalate into felonies and how bail violations crowd dockets.

“Judges and prosecutors are afraid of the next Leein Hinkley situation,” said Howaniec, who represented Hinkley at one point in the man’s criminal history. “But there needs to be more moderation when it comes to prosecution of nonviolent crimes, especially misdemeanors.”

THE SYSTEM ‘NEEDS AN OVERHAUL’

While justice system authorities see the problem differently based on their positions in the system, several suggested that regardless of any short-term answers to current frustrations, long-term answers must come in the form of a system overhaul.

“The state of our current criminal justice system is not well and needs an overhaul,” St. Laurent said. “There must be better ways to provide consequences adequately and fairly for one’s criminal behavior, especially for those repeat offenders who have zero regard for rules, our laws or the community itself.”

Citizens and business owners can reach out to their local representatives to share their frustrations with the constant cycle of reoffending and ask for legislation to better hold people accountable, he said.

Alexander said bail reform, such as eliminating cash bail for minor offenses, would help decrease jail populations while giving the judicial system room to prioritize its overload of cases.

“In the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services about a year and a half ago, we had … a person up in Aroostook County who had been charged with shoplifting. He’d been in jail for 40 days. Those things happen with oversights in the early bailing process, and they wouldn’t happen if we had a no-cash bail requirement for misdemeanor property-type cases,” Alexander said.

Howaniec added his thought that an overhaul of the judicial system is not enough.

“There is a correlation between poverty and high crime rates,” he said. “And until the politicians start fixing the root problems of poverty, there will not be much that the court system can do other than try to tread water.”

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.